|

|

|

|

The

History Pages

"Sorry

Sir, but that’s the best I can do. You’re lucky to get

a bunk at all.

Three men will have to sleep on the floor and two of

those are Colonels!"

|

|

|

|

|

| ../ main

page / history index / the lancastria |

|

The Lancastria Story... |

|

The evacuation of British troops from

France in 1940 did not end with Dunkirk. British forces were

still being rescued two weeks later when Britain's worst maritime

disaster of World War II took place. On the 17th of June 1940

the 16,000 ton Cunard liner Lancastria lay 5 miles off St

Nazaire and embarked troops, RAF personnel, and civilian refugees,

including women and children, who were being evacuated from

France, which was then on the verge of collapse. The exact

number on board may never be known, but almost certainly exceeded

6000; some estimates were as high as 9000. The Lancastria

was attacked and hit by bombs from German aircraft.

Auxiliary

Military Pioneer Corps which were wholly or partly aboard

Lancastria:-

• Companies numbered:

16, 26, 28, 32, 39, 40, 43, 46, 50, 52, 53, 61,

62,

63, 66, 67, 68, 73, 75, 82, 104, 108, 115, 208, 233.

• Base Depot Staff.

• HQ Labour Control.

• No. 1 Mauritius Company.

As Major

Scott-Bowden of the 53rd Company

Auxiliary Pioneer Corps boarded

with his men from the destroyer HMS Havelock, it was apparent

that Lancastria was becoming overcrowded with men. Once on

board he was instructed by the ship’s purser to proceed to

a second class cabin which had four bunk beds. Once inside

he discovered that seven other Officers were meant to be in

the same accommodation. He quickly returned to the Purser

who replied: "Sorry Sir, but that’s the

best I can do. You’re lucky to get a bunk at all. Three men

will have to sleep on the floor and two of those are Colonels!"

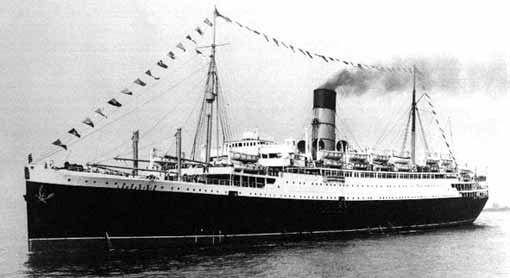

• The Lancastria in peacetime

The ship sank rapidly and according to the

estimate of the Captain, only around 2500 of those on board

were saved. Owing to the scale of the tragedy, Winston Churchill

forbade publication of the news in the interests of public

morale, and hence the story of the Lancastria has never been

generally known, although it is Britain's worst maritime disaster.

Two destroyers nearby, the HMS Havelock and the HMS Highlander,

began taking survivors aboard as did many merchant ships present,

such as the Glenaffaric, the Oronsay, the Fabian and the John

Holt. Many of the survivors were seriously wounded.

The New York Times broke the story, printing

some of the dramatic pictures of the disaster and was soon

afterwards taken up by the British press. The official report

however is still sealed until the year 2040 under the Official

Secrets Act. If it could be proved that the Captain

Rudolph Sharpe was ordered by Ministry of Defence Officials

to ignore his maximum load restriction there could be considerable

grounds for compensation claims against the British Government.

Currently the evidence for this remains under lock and key

for another 40 years.

It has been speculated that the primary reason the Official

Report has been supressed is that the Captain

of the Lancastria was instructed to load as many passengers as

possible and to "disregard international law on passenger limits."

It has not been clearly established who gave that instruction..

Given that that order was given however, and

also the fact that some of the survivors and, more

importantly, a significant number of relatives of victims, are

still alive, there could be significant cause for legal

action to be taken against the British authorities should it

ever be established who gave the loading order. Releasing the

documents of the inquiry could lead to significant compensation

being paid out. By 2040, it will be safe to assume that

most people directly affected, either through the loss

of a family member, or indeed, survivors affected will

no longer be around.

It is also worth noting the Authorities were

quick to place a D-Notice on the news of the sinking,

suppressing all

information about the disaster. Churchill claimed news would

damage morale, but when Churchill was subsequently asked

after the war why he had not lifted the D-Notice after the

Germans were finally defeated, he claimed he had merely

forgotten to do so.

• Taken from HMS Highlander

Picture courtesy of Mr Clements, Lancastria Association

• The Lancastria troopship in

its final movements. Those who managed to

escape overboard were engulfed by huge quantities of leaking

fuel oil

"Latitude 47.09, Longitude

2.20. I shall never forget that position that marks her grave.

Of the five thousand souls aboard her less than half had been

saved;

she sank like a stone and hundreds could not swim."

Harry Grattidge, personal

account

|

|

Lancastria Tragedy - from

The Pioneer magazine March 1947 |

|

The tragedy of the Lancastria is indeed a

memory one could well be without. I took 46 Coy on board her

early on that fatal day and we were, I believe, the first

troops to embark, followed by some 2000 RAF ground staff.

To my regret about 50 per cent of 46 Coy were lost and as

the Company was mostly composed of volunteer tradesmen it

was indeed a loss we could ill afford. I have since been told

that the total loss on that unfortunate ship was 3,300 and

I can well believe it. The great tragedy was that, after two

warning from reconnaissance planes, she was kept at anchor,

with almost 6000 on board, to be bombed like a sitting bird.

Major A G W Tonkin

of 669 POW Wkg 46 Coy, Greenford, Middlesex

|

| Tragedy of the Lancastria - from The Pioneer magazine June

1947 |

|

The sinking of the 16,000 ton Cunard White

Star liner "Lancastria" on the 17th June, 1940,

has been truly described as the greatest sea tragedy of all

time and, to the best of my knowledge, no official record

concerning it has been published. Indeed, although the facts

of her sinking were immediately known to the Germans, the

news of her loss was not made public in this country until

26th July, 1940. At the time of the occurrence I was serving

as the one and only subaltern with 46 Coy A.M.P.C., commanded

by Major D G Carr, and Capt (later Lt. Col, commanding 6 Group)

R.S Sim, MBE., as 2nd in command. We had left Rouen on the

8th June, presumably for evacuation, but we quickly received

instructions to take up a position of defence at le Neubourg,

the defence consisting of 46 Coy. A.M.P.C. plus one French

75 and a couple of machine guns! However we got away from

there and reached Lissieux and eventually arrived at Nantes.

My memories of Nantes are two fold, one being

amazement that the town appeared to be carrying on in the

same manner as if the Germans were still the other side of

the Maginot line and the other a grudging appreciation of

the efficiency of the Base Cashier who succeeded in getting

my account at Cox's debited with 500 francs, which I had drawn

as late at the 14th June ! On the following dat, at about

an hours' notice, we proceeded to an airfield near St. Nazaire

and there we hung about until the next evening when we, at

last, received orders to march to the docks. A tender was

just loading when I brought the Company alongside, only to

be told that it was practically full and there were no more

going out that night. I managed to squeeze 1 Sergeant and

15 O.R.s on board and they at least were saved the catastrophe

of the following day.

We camped out on the quay that night and

were on the first tender in the morning. Many other tenders

quickly followed and it was not long before the Lancastria

had been 5,000 and 6,000 on board. Even so we still remained

at anchor although enemy planes made two reconnaissance flights

over us in the early afternoon. When the actual attack was

made, at about 3.45pm., I had just gone to my cabin which

I was sharing with my O.C., so I have never been able to confirm

or refute the very general impression that the bomb came down

through the ship's funnel. The force of the explosion was

certainly terrific and completely spoilt two very good whiskys

and sodas which I had just poured out ! The ship almost immediately

took a heavy list and on making my way forward I found it

was impossible to do anything as the water was pouring in

and the place was an absolute shambles. The loss of life from

the explosion alone must have been very heavy. I, then made

contact with Capt. Sim (as he then was) and CSM (later Major)

F W Hall. The latter had the bad luck to get a dislocated

ankle, but we were able to get him to the upper deck. By this

time the ship was sinking rapidly (I believe she went down

within about 20 minutes of being hit), and the three of us

took to the water.

I made for an overturned life boat some little

distance away and thanks to the help of a Sergeant, who was

already there, I was able to clamber on to it, but the thick

oil on the water made swimming nearly impossible and doubtless

contributed to the loss of life. The enemy plane was still

hanging around, machine gunning men in the water. Fortunately,

the arrival of a RAF patrol drove him off. I would like to

pay particular tribute to the excellent morale of the men

who were in the water with me for over an hour, and the rescue

work carried out by the small French drifters and our own

destroyers was indeed splendid.

I was eventually picked up by the destroyer

"Highlander" and never shall I forget the wonderful

kindness of the Senior Service. They could not do enough for

us. The total loss on the Lancastria was subsequently given

me by a Staff Officer, who was onboard, as 3,300. In my own

Company the loss was approximately 50 per cent., and I believe

this was fairly general. On returning to England I was asked,

by GHQ., 2nd Echelon, to submit a report of the occurrence

to War Office, and on transferring to my copy I find that

the following A.M.P.C. Coys., in addition to my own, were

said to have been on board : 28, 50, 62, 67, 73 (of which

Major (later Lt.Col.) J H Courage was O.C.) 75 and 108.

In endeavouring to place on record my recollections

of this tragic event I would ask the indulgence of those of

my readers who were also on that ill-fated ship and whose

knowledge and memories are probably far better than my own.

Major A G W Tonkin

The following list of Other Ranks of

the Royal Pioneer Corps who lost their lives owing to the

bombing and sinking of the Lancastria is given as supplied

by War Office - It may not be complete - If anyone knows definitely

of any other Officer or Other Ranks who lost their lives in

this occasion please send details to me.

Details of Officer Casualties are not listed.

| Army No. |

Rank |

Name |

|

Coy |

| to appear shortly... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lancastrian Sinking - from

The Pioneer magazine March 1948 |

|

I read with interest of the sinking of the

Lancastria which was sunk off St Nazaire in the Bay of Biscay.

It was on June the 17th about 4.00pm,Monday it was, and she

was under water by 4.20pm, as I was one of the few who stood

on its side almost to the last trying to released a boat from

its bearings, when I noticed L/Cpl Kesson whom I noticed was

amongst the missing. He was clinging to an upturned boat just

before I jumped into the water with a few more pioneers of

the 67th Coy. I read the note of Capt C A Scott of Kingsland,

Newtown, Mon., dated 19 Sept 1947. At time of the Lancastria

he was a Lieutenant in the 67th Company. He mentions that

he last saw Sgt Thompson in the ship's canteen, well Sir,

I saw him sitting on the side of the ship as she lay before

going under, also was Cpl Butcher of the 67th and a Private

Page, who died, I believe on Wednesday morning in the hospital,

I was in at St Nazaire. I also saw two more of our Company,

but sorry to say I have forgotten their names, one was the

store-keepers assistant, the other one a private from Mablethorpe.

As it is so long ago I cannot remember their

names which I know would be of great help to you. I know they

are both dead as one tried to cling hold of the cabin door

to which I was clinging to with a boy of the ship's crew.

I helped him to get with some of his mates who were sitting

on the keel of the upturned boat, after which I was picked

up by a small fishing boat taking back men to docks at St

Nazaire. I was afterwards taken to the civilian hospital worked

by Nuns. It was June the 21st, 1940, when I and ten other

ranks of Buffs and Manchesters and a Belgian woman were taken

on board a British cruiser and landed at Plymouth the following

day. We arrived at a military hospital there for several weeks

treatment. I hope to give more information in the future,

when I can come across some of my old comrades.

Cpl A Pemberton

Pioneer Corps

|

|

Lancastria Survivors Re-union - from

The Pioneer magazine September 1951 |

|

Of the many service reunions that are held

it would be difficult to find one with such poigant memories

as that commemorating so great a tragedy as the bombing and

sinking of the S.S. Lancastria, off St Nazaire on the 17th

June 1940. Coming as it did, very soon after Dunkirk, it has

never excited any great comment either from the Press or the

BBC in spite of the fact that the loss of life was in the

region of 3,300, and thus becomes the greatest sea disaster

of all time. Incidentally, a list of about 400 other ranks

of the Royal Pioneer Corps who lost their lives appeared in

the magazine in June 1947, following an account I then wrote

of the disaster.

To mark the 11th Anniversary nearly a hundred

of the survivors mustered on the Horse Guards Parade and,

headed by a Band and Guard of the Streatham Unit, No 324 Sea

Cadet Group, marched to the Cenotaph where a wreath was placed

by Lt Col Goodwin. A service conducted by the Rev E Wilson

Carlile B.D., with a choir kindly provided by the Church Army,

included a special prayer and the beautiful hymn, "O

God our help in ages past."

At almost the exact hour that the Lancastria

was sunk the survivors again took to the water, but this time

it was on the firm deck of a Thames pleasure steamer and after

an enjoyable cruise the party were the guests of His Majesty's

Yeomen Warders at the Tower of London, and were personally

welcomed by the Governor, Col. E H Carkeet James, OBE MC.

After a specially organised tour of the Tower a very happy

time was spent at the Wardens Social Club and the survivors

had the great pleasure of meeting once again the Captains

of several of the ships that did such excellent rescue work

when the disaster occurred, including Captain W A Dallmeyer,

DSO., RN who commanded the destroyer HMS Highlander, and to

whom the writer will ever be under a debt of gratitude. The

party were also privileged to witness the unique and picturesque

"Ceremony of the Keys," which had its origin some

700 years ago and has several times been broadcast.

And Lang Syne brought to an end a memorable

day and the greatest credit must be given to Major C V Petit

for his excellent work as honorary organiser.

Major A G W Tonkin,

T.D.

Royal Pioneer Corps

|

|

British War Cemetery - Escoublac

- La Baule, Brittany - from

The Pioneer, September 1957 |

|

During a short holiday in Brittany

this year I took the opportunity of visiting the British War

Cemetary at La Baule. Needless to say the cemetery was in

absolutely first class condition, flowers and close cut grass

reminding one very much of an English garden. There are about

five hundred servicemen buried there including British, Canadian,

New Zealand and Polish airmen and commandoes. But my main

interest was in Lancastria men.

This ship you will recall,

sunk off St Nazaire on 17th June, 1940 when evacuating forces.

There were about 5,000 aboard her and about 2,500 were picked

up by other ships. Of the 2,500 drowned, most were trapped

in the Lancastria and went down with her. A number of bodies

were subsequently washed up on the beaches and were buried

by local people in their village cemetaries. After the war

the French Government gave land for the purpose of bringing

the bodies into one cemetery.

I was unable to find any grave

of a comrade known to me, but I took all the details I could

of members of the Corps whose last resting place is in this

lovely little cemetery and in case others might remember them

and might like to know where they are, I append the list here.

| Army No. |

Rank |

Name |

Date |

Age |

| 13003869 |

Pte. |

G Mills |

17.6.40 |

40 |

| 64682 |

Pte. |

J Ridley |

17.6.40 |

25 |

| 13002413 |

Pte. |

A E Brown |

10.5-10.7.40 |

50 |

| 13004153 |

Pte. |

W O'Neill |

17.6.40 |

28 |

| 13005966 |

Pte. |

H J Chapman |

17.6.40 |

36 |

| 1023063 |

Pte. |

W H Easterbrook |

17.6.40 |

42 |

| 3233186 |

Pte. |

P Langford |

17.6.40 |

41 |

| 13001316 |

Pte. |

H V Potton |

17.6.40 |

43 |

| 2188416 |

Pte. |

T E Smith |

17.6.40 |

33 |

| 13000584 |

Pte. |

P Khan |

17.6.40 |

35 |

| 4381206 |

Cpl. |

H Pattison, M.M. |

17.6.40 |

51 |

| 13005099 |

Pte. |

F Jackson |

17.6.40 |

45 |

| 13005010 |

L/Cpl. |

F G Harrison |

17.6.40 |

42 |

| 13004948 |

Pte. |

S Brook |

17.6.40 |

32 |

| 3179660 |

Pte. |

G A Melvin |

17.6.40 |

41 |

| 1001001 |

Cpl. |

A Cope |

17.6.40 |

40 |

| 13005225 |

Pte. |

A Apetu Larty |

17.6.40 |

43 |

| 2188527 |

Pte. |

B Axcell |

17.6.40 |

35 |

| 101269 |

Pte. |

R Bingham |

17.6.40 |

30 |

| 13001792 |

Pte. |

J Watt |

5.4.40 |

41 |

Major F H Blackburn

Royal Pioneer Corps

|

|

The Sinking of The Lancastria by

Stanley

Scislowski |

|

On Monday, June 17, 1940, the Cunard Liner, Lancastria, pressed

into war service as a troopship was anchored just outside

the harbour of St. Nazaire, France taking on thousands of

British troops in the evacuation of the British Expeditionary

Force threatened with annihilation or being taken in the bag

by the German armies rampaging their way through France. Two

weeks earlier, the last of the British and French troops had

been taken off the beach at Dunkirk in the almost unbelievable

overall evacuation of 335,000 British and French troops by

hundreds of craft of all kinds, from cruisers, destroyers,

ferries, river-boats, and small craft of every conceivable

size, shape and kind.

While France was accepting Hitler’s terms of surrender, the

highways and byways of the Pas de Calais outside the Wehrmacht’s

armoured encircling ring around Dunkirk were crowded with

Regiments of British Infantry and ancillary units streaming

towards St.Nazaire where, they were told, ships were waiting

to rescue them from the gaping jaws of captivity. Nineteen

vessels of varying size and types were either at dockside

or anchored in the open sea outside the harbour loading as

many troops as they could cram aboard. The Lancastria was

one of these ships, a single funnelled vessel of 16,243 tons

whose five decks could accommodate in peacetime close to 2000

passengers, but after being converted to troopship duties

it could, with reasonable comfort take on at least twice that

many. As it turned out, she accepted somewhere between 8000

to 9000, although there have been other estimates that were

well below these figures. Some said it carried no more than

5000 troops, although, according to reliable sources, the

higher numbers are closer to the truth. Amongst this great

crowd of fighting men were 38 civilians, 18 of them, workers

from the Fairey Aviation Corporation, along with a few women

and children.

The evacuation began on Saturday, June 16, with a five mile

queue of men inching forward to board ships either at dockside,

or ferried to ships anchored out in the approaches to the

harbour. Complete hospitals and Convalescent Depots were emptied

to become part of the vast exodus. Loading went on all night

long and through the next day. Tenders motored back and forth

ferrying troops between the dock and the Lancastria and other

ships standing by to take on troops in an urgency to beat

the German Armoured columns racing towards the city. The greater

danger, however, for the present, was the Luftwaffe bombers

circling over the harbour, taking turns in making bombing

and strafing runs at the ships below.

A seven ship convoy, commodored by Capt. H. Fuller aboard

the SS John Holt departed Newport the afternoon of June 16,

bound for St. Nazaire on the rescue mission, entering Quiberon

Bay at 7 a.m. the next morning where the ships were anchored

outside the harbour. About a mile away, another liner, the

Oronsay was also taking on a steady shuttle of troops. Shortly

before the Lancastria was hit, the Oronsay was struck by a

bomb, but sustained only minor damage and little loss of life,

and shortly the ship began moving out and was on its way to

England, its engines labouring under the heavy passenger load

it had taken on.

By four in the afternoon the last soldier had been taken

on board the Lancastria, squeezing himself into the incredible

press of men on the vessel’s open deck because every square

inch of cabin space had long since been filled. The ship was

within minutes of hauling up anchor and swinging about for

the quick run across the Channel to England and safety when

a lone JU 88 twin-engine bomber began its bombing run on the

helpless Lancastria. In the last seconds of its shallow dive,

several Bren gunners aboard the ship opened fire but failed

to drive the plane off. Four bombs plummeted towards the ship,

two hitting the sea nearby, while one smashed through the

dining salon and exploded in a lower deck, and the other,

according to witnesses, went straight down the funnel and

detonated in the engine room, both bombs blowing gaping holes

in the ships sides. They were mortal wounds, the damage so

extensive that the ship sank within fifteen minutes. The shortness

of time it remained afloat trapped most of those in the lower

decks, accounting for the reason why so many men went down

with her. Heavy loss of life also occurred amongst the hundreds

floating around on the sea with and without life-jackets,

on rafts, and clinging to whatever flotsam that they could

latch onto when the enemy planes swept in to machine-gun the

struggling mass of people in the water. The heavy blanket

of bunker oil released from the ship’s fuel tanks also contributed

to the death total.

It had been reported in the Daily Mirror of July 26,1940

that 2,823 had been lost, yet other sources claimed that the

total that went down with the ship or died in the water was

more like 5000. These same sources, namely counts taken by

army officers and ship’s officers as the men filed aboard

had the totals varying between 8000 to 9000 having been taken

aboard. Within a few minutes after the bombs struck the ship

began to list sharply to port and was down by the head, with

troops jumping overboard en masse. With the scarcity of lifejackets,

a high percentage had to go without, and with a good many

being non-swimmers, these unfortunate souls thrashed about

in the water for several minutes before slipping beneath the

surface to drown. Others, who were caught in the suffocating

blanket of bunker oil seeping from the ship’s hold, fought

to free themselves from the sticky mess enveloping them, their

eyes, ears, noses and throats eventually filling up, and in

a matter of minutes they too, gave up the struggle and let

the sea claim them. Those that wore lifejackets floated amidst

the debris of wood deck-chairs, packs, kit bags, bits of uniforms

and all sorts of other flotsam became targets for the bomber

as it swung around and made a low-level machine-gunning attack

on the helpless men. On the second pass, it dropped incendiary

bombs on the thick spread of oil around the ship, the murderous

crew hoping to set it on fire and incinerate them. Fortunately

the bombs failed to ignite the oil. The combustible mass simply

sputtered for a minute or so and went out.

When the bomber peeled off for a third strafing, two men

on a raft must have thought the situation was hopeless and

agreed to end their agony. The one with the revolver, pointed

it at his friend’s head, and then this man was heard to exclaim,

“Fire away!” A shot rang out, and within a second or two another

shot. The man ended his own life.

A short distance away, another drama unfolded. A lifeboat

crowded with survivors drifted into view of a group of people

on a raft. They saw an officer in the front with a revolver

keeping others away by threatening to shoot them. One man

in the water made several grabs at the boat, whereupon the

officer put the gun to the man’s head and fired. The man sank

out of sight. Not four seconds later, the officer himself

was shot from behind. He stiffened, then rolled sideways into

the sea and was gone. Desperation did strange and dreadful

things to people’s minds.

Although it was obvious the vessel would soon sink, there

was little or no panic. But, as one of the lifeboats filled

with women and other civilians was being lowered to the sea,

it got stuck halfway down. One overzealous

member of the Pioneer Corps,

thinking he could free the boat by cutting a rope with his

jack-knife succeeded only in causing the boat to drop at its

prow, throwing the terrified occupants into the sea.

It might be mentioned here the courage of those who, although

they knew they were within minutes of stepping over the threshold

into eternity, raised their voices in song as they stood on

the lowering decks. “Nearer My God To Thee” was not the song

sung on the Lancastria as the doomed passengers on board the

Titanic were supposed to have sung as that great ship was

going down in the icy North Atlantic in 1912. The soon-to-be-drowned

souls on board the Lancaster sang more cheerful tunes, songs

like ‘Roll Out the Barrel’, ‘Hanging Out the Washing on the

Siegfried Line’, and as the end drew nearer, they broke into

‘There’ll Always Be An England’. Closer to the ship’s stern,

another group, their voices clear and unwavering sang, ‘God

Be With You Till We Meet Again’.

Many were the heroic acts that took place in the short fifteen

minutes between the time the bombs hit and the ship’s disappearance

beneath the waves. A lone Bren gunner somewhere unseen on

one of the decks kept popping off short bursts at the German

planes that kept sweeping, its wing-guns lashing out at the

men bobbing about and struggling in the oil-smeared sea. This

brave man, could have, like those around him, made an attempt

to leave the ship to save himself, but he chose to stay at

his weapon even as the water closed in over him. The truly

sad part of this man’s sacrifice was that no one would ever

know his name—a hero who will forever remain unknown.

Fear can sometimes bring about miraculous results, as when

an RAF officer who was about to jump into the water, overheard

a man next to him bewailing the fact that he couldn’t swim.

The officer, cuttingly replied, “Well, now’s your chance to

learn.” Shortly thereafter as the officer treaded water, this

self-same individual who couldn’t swim, went by him like a

torpedo. His stroke, that of an Olympic champion.

Fear can also do strange and awful things to men’s minds.

One panic-stricken man in the water went berserk as he tried

to tear the life-jacket off another man, and then fought to

join the group of six people clinging together in a circle,

three having lifejackets, the others had not. By this means

the ‘haves’ managed to save the ‘have-nots’. But now as the

manic one thrashed and flailed away with his arms trying to

wrench a jacket off one of the group, a fierce struggle ensued.

As one of the group later explained, “Had the fellow been

calm, we could have supported the extra burden. But since

he was a menace to our own hopes of survival, we had to fight

him off, after which he swam over to another man and fought

him for possession of the man’s lifejacket The outcome of

this man’s demented effort to save himself is not known. One

might ask here, “Why is it that some people, on the approach

of doom can face it with stoicism or calm resignation, while

others go into paroxysms of weeping or uncontrollable violence

as the end draws near?” The answer defies conclusion.

Besides the lone Bren gunner who stayed at his post until

the seas closed over him, there were other isolated acts of

heroism going on. Like the naked man covered completely in

black oil who dove time after time into the sea from the safety

of the rescuing ship to bring floundering people to its side

where they could be hauled aboard.

And then there was the poignant scene of a mother, and her

tiny baby being thrown into the water when a lifeboat capsized

crying out to others drifting nearby, “My baby! My baby! Please

find my baby!” Back came the answer, “It’s all right, Ma,

we’ve got her,” as they held her baby well above the water.

As the Lancastria was settling rapidly by the head, ships

nearby—the trawler Cambridgeshire, the destroyers Havelock

and Highlander, the cargo ship John Holt and other ships responded

to the urgency by moving in and pulling survivors out of the

water, many of those picked up out of the water were heavily

covered in oil or suffered acutely from exposure in the cold

water of the Channel. They rescued, as the Daily Mirror reported

2,823 out of a total of close to 8000 passengers that had

been aboard. All others, over 5000 of them went down with

the Lancastria. Exact totals will never be known. Suffice

it to say that the sinking of the Lancastria was the single

greatest marine(not naval) disaster suffered by the British

in WW II, and for the sake of morale at a time when that morale

wavered under the punishing blows of defeat in France, publicity,

through necessity, was minimized. As the war progressed and

other disasters occurred, one upon the other, the loss of

the Lancastria was soon forgotten, except in the many households

throughout the British Isles where the loss of a loved one

would never be forgotten.

Stanley Scislowski

13-08-2001

(reproduced

with kind permission - thanks Stanley)

|

|

Pioneer Accounts - from

The Forgotten Tragedy by Brian James Crabb |

|

Lieutenant R Haynes, AMPC, narrlow avoided

death. He had been standing two yeards from the hatch when

the explosion occurred and was thrown to the deck. He relates

his story: "As I lay there waiting for the debris to

fall I began to pray. It must have been only seconds, but

it seemed like ages and I prayed like hell. Then I felt a

blow against my back. A rifle had hit me. I was relieved it

was not a Bren gun !

Lieutenant R Haynes

AMPC

|

A company sergeant of the Auxiliary Military

Pioneer Corps, who had been allocated to one of the holds,

related his story: "I gave the order to man the hosepipes,

for smoke was coming in the hatch. It was impossible to obey,

because the troops were jammed so tight in the alleyways.

Just then the ship gave a sudden lurch to port until she was

listing at an angle of 45 degrees. We were thrown off our

feet. From the bridge came the order: "Every man for

himself," and I chucked hatchboards over the side to

act as rafts when we got into the water. By this time the

ship was beginning to sink and her propellers were right out

of the sea... as two of the lifeboats were dropping down the

towering side of the Lancastria, they capsized. One had about

120 people on board including two French women and two children,

aged about five. They were flung into the water. One woman

flung her baby into the water and dived in after it; she was

a strong swimmer, and after picking up the child she made

off to one of the lifeboats...

Forward was a soldier with a Bren gun rattling

away with all he'd got. He stuck it out even when the water

was up to his waist. His gun was silenced only when he was

washed away from it. A grand lat. I hope he was saved. Just

before the ship capsized and went down, some of our men...

(laughed in the face of death) (we called ourselves The Thin

Red Line) and scrambled on to her uppermost side. There they

stood, ... (with an immaculately dressed British officer coolly

smoking a cigarette) knowing that they had no chance. They

went down like brave men, singing 'Roll out the Barrel...

(let's have a barrel of fun) !

Company Sergeant

AMPC

A sergeant of the AMPC had been in the stokehold

during the attack. Tracing his way into the accommodation

area he rushed to the side of a French woman and her eight

year old child. He assisted them up a companionway, which

was hampered by escaping steam from fractured pipes. To avoid

getting burnt they held handkerchiefs over their faces. He

eventually got them aboard a lifeboat and was then told to

join them.

Sergeant

AMPC

|

|

Photographs of The Lancastria by

Frank Clements |

| In 1940 Frank Clements was a 30-year-old

volunteer onboard the HMS Highlander, a destroyer that was being

used to ferry troops from Saint-Nazaire harbour to the anchored

Lancastria. His pictures tell the tragic story of the Lancastria

and are the only photographs of the stricken vessel's final

moments. |

|

Navy personnel were not allowed to

take cameras on board but as a volunteer in the naval stores,

he managed to keep his camera with him wherever he went. His

younger brother Arthur Clements, now 84, says: "He was

a photographic nut. He took thousands of 'prints' as he called

them of his war experiences all over the world." But

as well as taking pictures he also played his part in the

rescue operation, downing his camera to help survivors. "He

did all he could," recalls his brother. "He even

pulled a little baby out of the sea."

He talked afterwards about the soldiers who

had been ordered not to abandon

their rifles. He watched them drowning under the weight of

their heavy weapons and said he shouted at them to let go

of them. Sadly many didn't listen." |

|

|

Valerie Billings of the Portsmouth Naval

Museum, who interviewed Mr Clements before his death in 1999,

says it was an enormous stroke of luck that he was able to

take the photographs. "It was an amazing coincidence,

firstly that he had a camera on board at all. Secondly, he

had no film for the camera but happened to meet a sailor on

his way to Saint-Nazaire who swapped him a camera film for

a pair of socks from the NAAFI stores and it was with that

film that he took these pictures." |

|

When he returned to the UK, Mr Clements handed over prints

of his photographs

to a man he met in a pub. The pictures were then sold to the

press, although Mr Clements never made any money from them.

The pictures have now become invaluable to the Lancastria

Association in their campaign to make the story of the doomed

ship more widely known. The Association's Robert Miller, who

headed out on a pilgrimage to Saint-Nazaire on

the 60th anniversary of the disaster, says: "The photographs

are extremely important, priceless in fact, to us and to the

whole fabric of the story." "If it wasn't for the

fact that Frank Clements was on board the Highlander and that

he was a keen photographer, there would be no pictures of

the disaster whatsoever." |

|

• Battle-weary troops wait •

They were loaded onto navy destroyers and

on docks at Saint-Nazaire ferried

to the giant troopship HMT Lancastria

|

|

• Estimated 6000 servicemen, plus a number of •

Boats like the HMS Highlander loaded people

civilian woman and children were taken onboard

onto the Lancastria until it was

overflowing

|

|

• At 1400hrs the anchored Lancastria, seen here •

At 1557 she was struck by bombs below the

in background, was attacked by enemy aircraft waterline

which ruptured the boat's fuel tanks

|

|

• Others were burnt as oil was ignited by flares •

Rescue boats picked up survivors under fire

from the few lifeboats. By 1615hrs it hadsunk. from

enemy aircraft.

|

• Exhausted and covered in oil, many were •

Of the estimated 6,000+ people onboard the

loaded onto ships bound for the UK. Lancastria,

less than half survived

|

|

Lancastria Survivors Association |

| After the war the 'Lancastria

Survivors Association' was set up by Major Peter Petit, which

brought together the then-known survivors, however, this Association

lapsed with Major Petit's death. The Association was revived

in its present form in 1980. We meet our objectives by holding

meetings both on a national and a regional basis and by making

pilgrimages to the St Nazaire area, visiting cemeteries where

victims are buried, and the wreck itself.

The membership now includes over 160 survivors of the disaster,

some now living as far away as North America, Africa, and

Australia and New Zealand. The exciting thing is that they

are still finding survivors, some via the Internet. The prime

meeting each year is held on the first Sunday after the 17th

of June at St Katharine Cree Church, Leadenhall Street, in

the City of London. The Annual General Meeting is preceded

by a ceremony at the Merchant Navy memorial on nearby Tower

Hill and is followed by a remembrance service at the church.

Other activities include an annual visit to the National Arboretum

at Alrewas in Staffordshire where Merchant Navy losses in

World War 2 are remembered by a convoy (of trees) headed by

the Lancastria.

In the year 2002 they are making a another pilgrimage to

St Nazaire to mark the 62nd anniversary of the tragedy and

there are visits in the planning stage to the museum at RAF

Digby, in Lincolnshire, which has a section devoted to the

Lancastria, and the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool

to see the Lancastria display there.

Membership of the Association is now open to any person who

wishes to remember the sacrifices made in, or resulting from,

the action of the 17th of June 1940.Details can be had from

the Association's Secretary:-

Lancastria Survivors Association

Association

Secretary

Robert

Miller

2

Ash Road

Sandwich

Kent

CT13

9JA

Email

the Association

Survivors' stories are printed in The Loss of 'Lancastria'

by J L West (£4.00) and The HMT Lancastria Association

Narratives, (£10.00). Both are available from the Association

:-

Lancastria Survivors Association

Association

Treasurer

Colin

Clarke

14

Coxswain Way

Selsey

Chichester

PO20

0UA

|

• The Lancastria memorial

on the sea front at St. Nazaire

"Opposite this place lies the wreck of the troopship

Lancastria sunk by enemy action on 17 June 1940 whilst embarking

British troops and civilians during the evacuation of France.

To the glory of God, in proud memory of more than 4,000

who died and in commemoration of the people of Saint Nazaire

and surrounding districts who saved many lives, tended wounded

and gave a Christian burial to victims.

We have not forgotten. HMT ‘Lancastria’ Association, 17

June 1988.’’

|

|

Related Links |

Lancastria Association of Scotland Lancastria Association of Scotland

Lancastria

Association Lancastria

Association

|

|

|

|

|